Rescuing superconductivity

From a paper in Nature Reviews Physics, December 19, 2024:

One of the forefront fields of modern superconductivity research is that on hydrides at high pressures. Over the past few years, this research has attracted considerable publicity, of which a substantial fraction has been negative. Scientific fraud has been committed and exposed, and arguments continue about specific aspects of data presented in some other papers. Among all the noise that is being generated, one might lose sight of the big-picture question of whether the field is on solid foundations or not, that is, whether high-pressure hydrides host superconductivity at all. Here, we readdress this central issue. We select and critically examine what we identify as six key papers on the topic. We have all spent substantial portions of our careers working on superconductivity, so hope that the conclusions that we reach will carry at least some weight. We also decided to include among our authorship team only people who have never worked directly on hydride superconductivity, so that our examination of the scientific facts can be as impartial as possible. We conclude that it is overwhelmingly probable that the phenomenon of hydride superconductivity is genuine.

It's intriguing such an exercise had to be undertaken. It's yet another reminder that practising science isn't simply a matter of following the facts. Science is part of the world, not separate from it, and is affected by what others think of it, especially based on perceptions of trustworthiness, self-correctability, and integrity. Self-correctability in particular went out the window the moment the holes in the Dias/Salamat saga became clear, followed by integrity. Imagine discovering a groundbreaking new natural phenomenon: usually such things revitalise fields looking for a breakthrough, but here, the field became marred by a slew of bad papers that shrunk funding opportunities and rendered young researchers trying to enter or already in the field nervous about their future.

In fact the self-correctability and integrity issues were compounded by the actions of the journals that published the problem papers. Nature and Physical Review Letters both have submissions peer-reviewed. The process of peer review is designed to check whether the data provided match the conclusion provided, not the integrity of the data. However, the data the journals reviewed before publishing the papers was also the data independent experts reviewed to find flaws, consequently leading to the retractions. Even more: one of the papers, purporting to show superconductivity in LuNH and published in Nature in March 2023, didn't contain enough evidence to support the conclusion, which the journal's review missed as well. A Nature news feature reported in September that year:

Critiques started appearing as soon as the Nature paper was published. One major line of criticism is that the Rochester team didn’t provide enough evidence to show that resistance does go to zero in its material. Dias and his colleagues state in the paper that they removed “small residual resistance” from some of their electrical measurements, but critics argue that it should not be necessary to remove background for these types of measurements, given clean readings of both a sample’s current and voltage. The problem with removing a background, says Sven Friedemann, a physicist at the University of Bristol, UK, is that it implies that the raw data do not go to zero — and therefore don’t show superconductivity.

The same feature also quoted two scientists saying Nature’s retraction of a carbonaceous sulphur hydride paper in 2022 was "not strong enough".

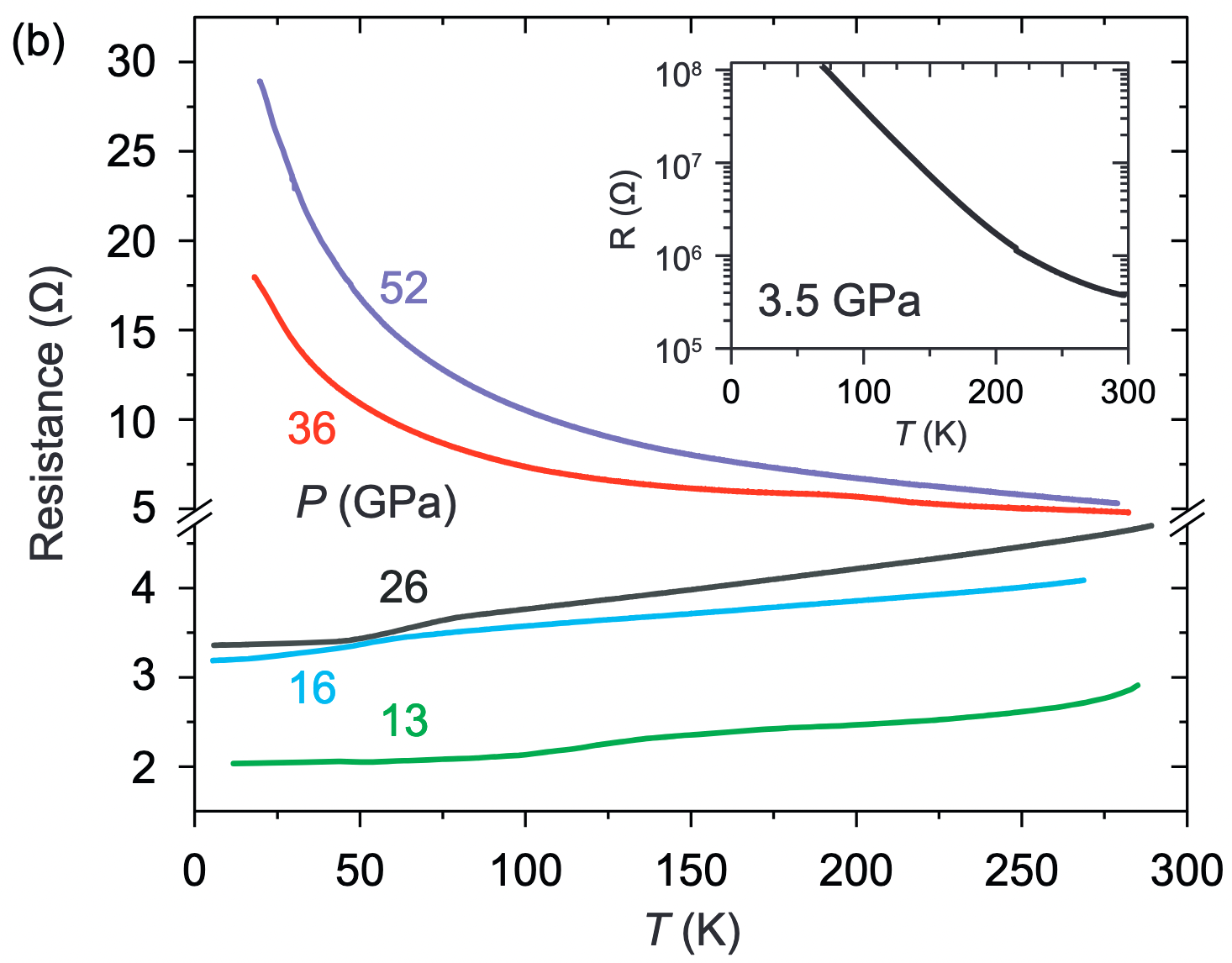

The names of many of the authors of the review should be familiar to people who have been following the Dias/Salamat saga, including Peter Hirschfeld, Steven Kivelson, Andrew Mackenzie, and Subir Sachdev. The review reportedly began with the two possible outcomes — hydrides display superconductivity versus hydrides don't — being equally probable and concluded in favour of the former after assessing the results reported by multiple groups. While the nominal definition of superconductivity alludes only to the fact that a material's electrical resistance drops to zero, condensed-matter physicists perform four tests looking for different features. One is zero electrical resistance; another is that the material's magnetisation varies through a particular pattern. On this count the reviewers assessed data from only one group, that of Mikhail Eremets & co. in 2022.

Yet another familiar name, Jorge Hirsch, has already expressed his disapproval towards the review. "I was surprised and disappointed to see this. I speculate [they wrote] it because hydrides being superconductors would establish the validity of BCS theory, in which they firmly believe," he told Physics. A bit of relevant background here is that Hirsch is a detractor of the popular BCS theory of superconductivity and a proponent of his own holes theory. While Physics writes that he's already flagged some problems with the Eremets et al. paper, it doesn't say the Eremets et al. paper raised significant doubts about the validity of his holes theory — which is to say both the study and Hirsch's idea could be flawed rather than the study alone. Overall, if science is to remain trustworthy, scientists need to undertake exercises like this, conducting — while being seen to be conducting — impartial reviews of the prevailing evidence and considering whether it makes sense to continue working in fields beleaguered by the influence of some dishonest exponents.

I only hope reviewers will also take a closer look at the roles journals and their misguided incentives — and the still largely blind trust the global scientific community places in them — play in sustaining scandals in science.