Solutions looking for problems

There’s been a glut of ‘science projects’ that seem to be divorced from their non-technical aspects even when the latter are equally, if not more, important – or maybe it is just a case of these problems always having been around but this author not being able to unsee it these days.

An example that readily springs to mind is the Bharati intermediary script, developed by a team at IIT Madras to ease digitisation of Indian language texts. There is just one problem: why invent a whole new script when Latin already exists and is widely understood, by humans as well as machines? Perhaps the team would have been spared its efforts if it had consulted with an anthropologist.

Another example, also from IIT Madras: it just issued a press release announcing that a team from the institute that is the sole Asian finalist in a competition to build a ‘pod’ for Elon Musk’s Hyperloop transportation concept has unveiled its design. On the flip side, Hyperloop is a high-tech, high-cost solution to a problem that trains and buses were designed to address decades ago, and they remain more efficient and more feasible. Elon Musk has admitted he conceived Hyperloop because he doesn’t like mass transit; perhaps more reliably, his simultaneous bashing of high-speed rail hasn’t gone unnoticed.

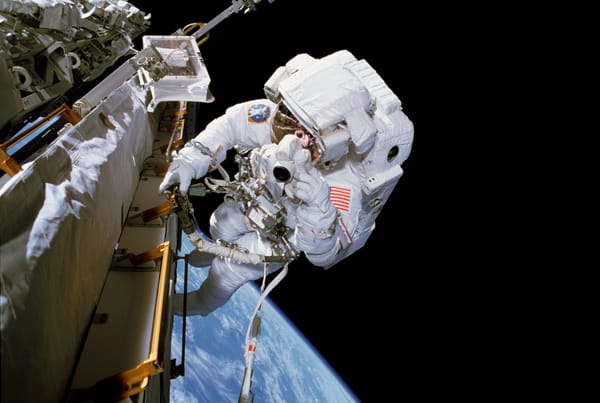

Here is a third example, this one worth many crores: the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) wants to build a space station and staff it with its astronauts. The problem is nobody is sure what the need is, maybe not even ISRO, although it has been characteristically tight-lipped. There certainly doesn’t seem to be a rationale beyond “we want to see if we can do it”. If indeed Indian scientists want to conduct microgravity experiments of their own, like what are being undertaken on the International Space Station (ISS) today and will be on the Chinese Space Station (CSS) in the near future, that is okay. But where are the details and where is the justification for not simply investing in the ISS or the CSS?

It is very difficult to negotiate a fog without feeling like something is wrong. We built and launched AstroSat because Indian astronomers needed a space telescope they could access for their studies. We will be launching Aditya in 2020 because Indian astrophysicists have questions about the Sun they would like answered. But even then, let us remember that a (relatively) small space telescope is too lightweight an exercise compared to a full-fledged space station that could cost ISRO more money than it is currently allocated every year.

Sivan’s announcements are also of a piece with those of his predecessors. In fact, the organisation as such has announced many science missions without finalising the instruments they are going to carry. In early 2017, it publicised an ‘announcement of opportunity’ for a mission to Venus next decade and invited scientists to submit pitches for instruments – instead of doing it the other way around. While this is entirely understandable with a space programme that is limited in its choice of launchers, this pattern has also prompted doubts that ISRO is simply inventing reasons to fly certain missions.

Additionally, since Sivan has pitched the Indian Space Station as an “extension” of ISRO’s human spaceflight programme, we must not forget that the human spaceflight programme itself lacks vision. As Arup Dasgupta, former dy. director of the ISRO Space Applications Centre, wrote for The Wire in March this year:

… while ISRO has been making and flying science satellites, … our excursions to the Moon, then Mars and now Gaganyaan appear to break from ISRO’s 1969 vision. This is certainly not a problem because, in the last half century, there have been significant advances in space applications for development, and ISRO needs new goals. However, these goals have to be unique and should put ISRO in a lead position – the way its use of space applications for development did. Given the frugal approach that ISRO follows, Chandrayaan I and the Mars Orbiter Mission did put ISRO ahead of its peers on the technology front, but what of their contribution to science? Most space scientists are cagey, and go off the record, when asked about what we learnt that we can now share with others and claim pride of place in planetary exploration.

So is ISRO fond of these ideas only because it seems to want to show the world that it can, without any thought for what the country can accrue beyond the awe of others? And when populism rules the parliamentary roost – whether under the Bharatiya Janata Party or the Indian National Congress – ISRO isn’t likely to face pushback from the government either.

Ultimately, when you spend something like Rs 10,000-20,000 crore over two decades to make something happen, it is going to be very easy to feel like something was achieved at the end of that time, if only because it is psychologically painful to have to admit that we could get such a big punt wrong. In effect, preparing for ex post facto rationalisation before the fact itself should ring alarm bells.

Supporters of the idea will tell you today that it will help industry grow, that it will expose Indian students to grand technologies, that it will employ many thousands of people. They will need to be reminded that while these are the responsibilities of a national government, they are not why the space programme exists. And that even if the space programme provided all these opportunities, it will have failed without justifying why doing all this required going to space.