The turtle walk

Last night, I saw a just-hatched olive ridley, measuring no more than 6-8 cm in length, swim back into the ocean after being set on the sand by a worker. Because of the turtles’ choice to lay eggs on the beaches off Chennai, there is a significant chance that the eggs will be sniffed out by dogs or poachers, and the young ones killed for their meat. Instead, these conservationists, the turtle-walkers, patrol a 14-km stretch along the coast every night during the egg-laying and hatching seasons. When they find hatchlings, they are guided into the ocean by setting them down on the sand, shining a torchlight at them from close to the water, and ensuring they follow the light and don’t strike land again – although this practice is most obviously for the entertainment of the volunteers/onlookers invited to walk with them.

The olive ridleys lay their eggs in the months of February and March, which means the hatchlings will be out after a 45-55 day incubation period just before the hotter days of summer are on. Higher temperatures (over about 35 degrees Celsius) are likely to kill the unhatched ridleys because microbial activity associated with decomposition of the eggs kicks in. At the same time, the gender of a newborn is determined by the same incibation temperature: if between 31-32 degrees Celsius, the clutch is solely female; if between 29-30 degrees Celsius, the clutch is a mix of males and females; if below 28 degrees Celsius, the clutch is solely male. I suspect some degree of antecedence in this pivoting about a temperature to ensure the birth of solely females as global temperatures rise. This conjecture is predicated on the assumption that each male olive ridley can mate with multiple female ones.

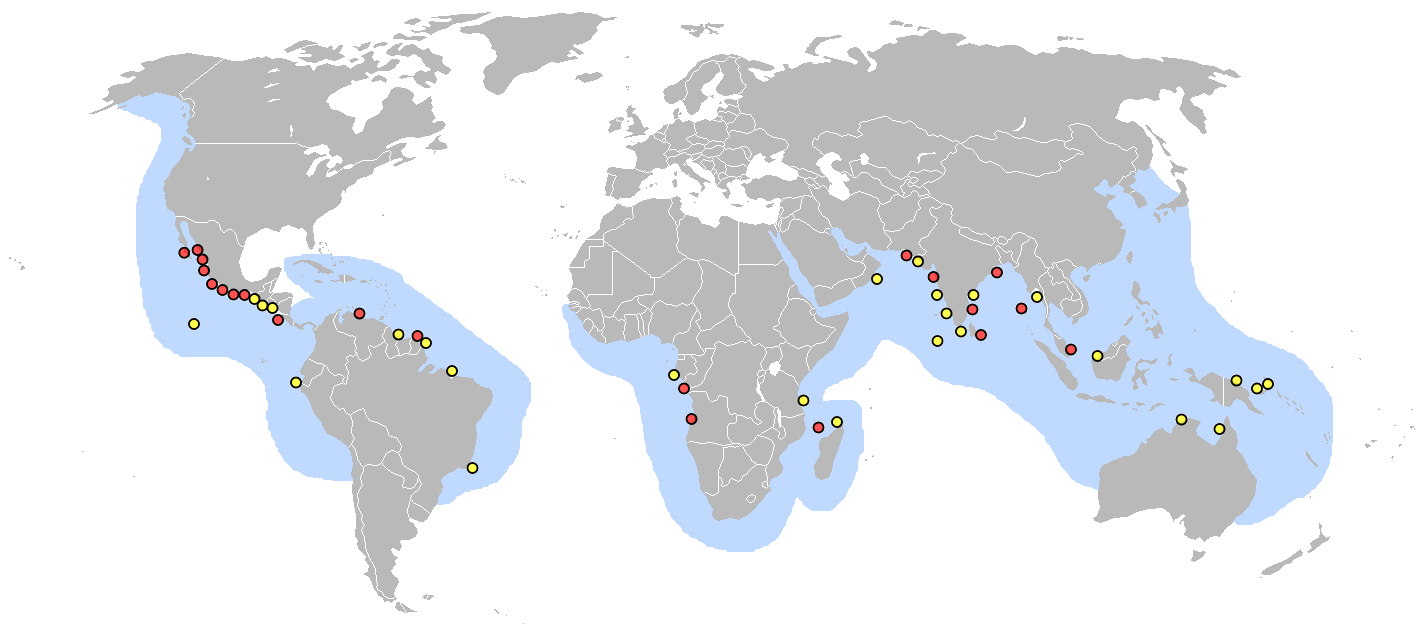

Another interesting, and temperature-related, thing about the olive ridleys is the location of their major nesting grounds: the western coasts of Costa Rica, Nicaragua and Mexico, and along the eastern coast of India (along the northern reaches of the Indian Ocean). There are other sites off Angola, the Congo, and Indonesia as well, but the major ones lie between the Tropic of Cancer and the latitude 15° south of the equator. These are warm climes. On a related (and opposing) note: one of the turtle-walkers suggested that the laying of eggs occurs during nights and before high summer, when the ambient temperature is lower overall and significantly lower after sunset. When asked why the ridleys choose sub-tropical regions for nesting, the walkers conjectured it could be so because these regions are historically their birthplaces. That seems too simplistic an explanation. Moreover, with regions farther from the equator becoming warmer over the last five or so decades, we’ll soon see if ridleys nest on newer grounds.

(When I run a Google Scholar search for if migration patterns of the Ridleys have changed over the last few centuries, almost nothing comes up. If patterns haven’t shifted, then the birthplace guess could be true. If the patterns have shifted and become more diffuse… well, have they?)

Apart from these factual dwellings, the turtle walk is a brilliant experience even though the chances of coming across any eggs or the ridleys themselves are low. Though the walkers themselves patrol a 14-km stretch, the nighttime volunteers pace a 4-7-km stretch from Neelankarai in the south to the Besant Nagar beach to the north. As the western facade gradually evolves from sites of gorilla urbanism to early-rising fishing hamlets, the bay to the east remains relentlessly unchanging, although as the night grows older, the strong landward breeze gradually weakens. Crabs (of the family Carpiliidae) are also a common sight, with as many as hundreds at a time visible scuttling along the shoreline. Another added bonus is for amateur stargazers: the skies, if they’re clear, have far more stars on display in the dead of night, far removed from bright terrestrial sources of light, than would be visible at any time of any day from even a kilometre inland.

And even if you end up having a 4-km stroll doing nothing at all, the sight of a dozen olive ridleys at the end swimming back into the sea could make your day.